In the final days of August 2021, the US completed its withdrawal from Afghanistan after 20 years. As the Taliban retook control of the country, one Afghan family was forced to make a decision about their future.

Four decades before, they had welcomed an American into their family. Now, it was his chance to return the favor.

Jabar

In 1978, there was a coup in my country. The Communist party took over in what is now called the Saur Revolution. It all happened very quickly. I remember walking back into my family home after saying my goodbye to David, a man I considered to be my brother. My whole family stood inside weeping.

My name is Jabar, and I am proud to be from Afghanistan. I was raised in Kandahar, in the country’s south, and graduated from the university in our capital, Kabul.

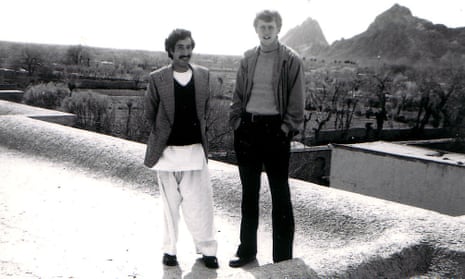

After university, I chose six years of teaching in place of the mandatory two years of military service. The government placed me at a boys’ school in my home town in 1976, and it was there that I met David Wilson, an English teacher volunteering with the American Peace Corps.

We became friends pretty quickly. I learned that he liked basketball, so I invited him to play with the team at our school. Since our houses were only about a 10-minute walk from each other, we would ride our bikes together to and from school. Wilson would also come to my family’s home to play cards and chess for hours.

In Afghan homes, there is usually a separate room to receive guests, and only the men of the family are allowed to greet them while women must hide their faces. But after some months, my father had grown close to Wilson. One day, he invited my mother, my sisters, and all of my other relatives to meet him. He said that from that day on, Wilson was his son, and that my female relatives should no longer hide their faces from him. He was able to come into our house without knocking.

Years later, when my mother was dying, she placed five photos of her sons in front of her; one of them was of Wilson.

When the Communist coup came two years after meeting David, everything was turned upside down. The Russian-backed party started to label all Americans as “imperialists” and said that imperialists were their only enemy.

The national security forces became suspicious of my friendship with Wilson. They thought that I was spying for the US, so they searched my house and held and questioned me for a week straight. Wilson, who was back in the US by then, heard about this and asked me to stop writing to him. It was too dangerous, he told me. I did not like that. We lost contact for almost a decade and a half.

Years later, in the mid-1990s, I was working with the UN, in Herat. At the time, different groups of mujahideen were fighting for control of Kabul and Afghanistan. One day, I got a call telling me to immediately report to one of the high-up officers. I thought I must have done something wrong – the five minute drive to the central building felt like five days; I had no idea what I had done for this to happen. I was asked if I knew any Americans. I said no, and then he asked if I was sure. I told him that during the Communist regime, many families had lost loved ones, and in our case, it had been my American brother. At the time, I didn’t even know if Wilson was still alive.

All of a sudden, the officer pulled out a letter from behind the desk. I immediately recognized Wilson’s handwriting. I kissed the envelope, and left without saying goodbye: I didn’t want the officer to see me crying.

From that day on, we started to communicate through letters and phone calls.

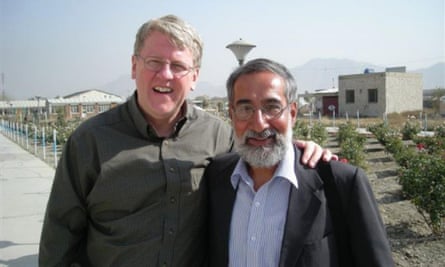

In 2002, I was sent to Germany for a work training and Wilson flew in from the US to meet me. After more than 20 years, we reunited in a hotel lobby. I couldn’t control my emotions. We walked for hours together. Today, all of my children call him “Uncle Dave”. My youngest son even chose to study architecture in Nebraska. He broke his leg while there, and Wilson took care of him for an entire two months.

My wife and the rest of our children left my beloved country shortly after the Taliban took over last year. I did not want to. I did not see myself as a refugee. I felt a need to work for my Afghanistan, not to leave it. But I realized I can only do this if I am alive.

One of my daughters moved to Nebraska with her husband and daughter, and they live five minutes from Wilson – and he helped them find passage. My older son is in Germany, and my other daughter is in Brazil. She hopes to continue on to the United States, too, once her asylum claim is processed.

As of a few months ago, I have been in Italy, seeking asylum with my wife.

But I don’t want to be under the protection of the United States. They destroyed Afghanistan and stole all the wealth from my country; they did not come to build it. There is no place for Americans in the heart of the Afghan people. To this day, Wilson is the only American I have a relationship with, and he will always be my brother.

David

My name is David Wilson. As a kid, growing up in the early 1960s, I was completely taken by John F Kennedy. To this day, I still have my JFK scrapbook full of old newspaper photos. On the day he created the Peace Corps, in 1961, I remember thinking: “Wow, someday I want to do that.”

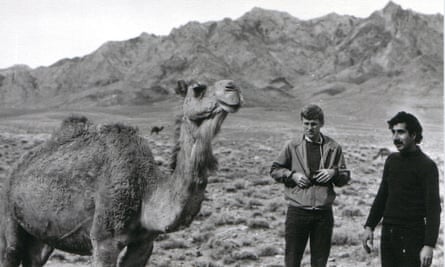

In 1976, when I was 21, I walked into a Peace Corps recruiting office in Kansas City, and applied. There were only two positions open: one in Thailand and another in Afghanistan. The only thing I knew about Afghanistan, like many Americans at the time, was that its athletes walked out first at the Olympics Parade of Nations. But in Thailand, I knew they had snakes. So that day, after searching with the recruiter on the map, I chose to go to Afghanistan.

In January 1977, I left my home state of Nebraska on a flight to Kabul, where I spent a few months training. As soon as a position opened in Kandahar, I applied. A lot of people in Kabul, including the Afghans, warned me not to go; they said the people there were dangerous drug addicts and thieves.

I arrived in Kandahar and moved into a small apartment in the city’s south-west. For the first months, I spent about six hours a day at the school where I taught English. I had kind, curious fellow teachers, but once school was over, we didn’t interact much. I was pretty lonely.

I soon realized that if I didn’t find a friend soon, I wasn’t going to make it through my service. Sitting in a big square with the other teachers one day, I went down the line in my head, trying to decide who I was going to befriend. I landed on a man named Jabar. The students didn’t respect all of their teachers, but I knew that they all liked him. He also put up with my bad Pashto, which I was still learning.

We started to ride our bikes to school together. We played chess and cards at his house. His father even announced to their family that I was now officially his fourth son. When Jabar traveled to Herat to ask for the hand of his future wife in marriage, he brought me with him. But things changed one day in April 1978.

I was at Jabar’s home when his student knocked on his door and told us to turn on the radio. There was military music playing; the same music that had played five years earlier, when the prime minister, Daud Khan, had overthrown the monarchy to become Afghanistan’s first president. Jabar knew that this time it was the Communist party, and that Americans might be in danger. Less than a year later, the American ambassador to Afghanistan, Adolph Dubs, would be killed in Kabul.

I had met Dubs in Kandahar when he came to visit. Jabar and his wife made me stay with him until the situation stabilized. Back home in Nebraska, my father got a call from the Peace Corps. They told him that 100% of volunteers in Afghanistan had been accounted for … except for me. Finally, after about four days, I was able to board a bus to Kandahar, and from there to Kabul.

I left the country in December 1978. Originally I had wanted to extend my service, but I realized me being there was putting the Afghans I loved in danger. It wasn’t until 2002 that I would see Jabar again.

Today, our conversations are like those of two brothers. We check in on each other’s families all the time. The politics of our countries don’t get in the way of that. Things really came full circle last September, when the US pulled out of Afghanistan.

Jabar’s daughter, her husband, and their two young sons had gone to the airport in Kabul, but after almost two days of waiting couldn’t get on a flight. I have some contacts at the US military, so I was able to find them an escort back to the airport and they left safely. Twenty-four hours later, that suicide bomber attack happened at the same gate they had just left from. Luckily, the family now lives five minutes away from me in Lincoln, Nebraska, with jobs and an apartment. A friend and I worked together to get Jabar’s other daughter and her family to Brazil on humanitarian visas. They’re hoping to end up in the US as well.

When I think of Jabar’s family, who adopted me all those years ago in Kandahar, how could we have imagined that their great-grandchildren would be living around the corner from me in Nebraska? I walked away from Afghanistan with a four-generation relationship with a wonderful family. There’s been so many times where it looked like that wasn’t going to happen. But here we are, 40 years later, all because I needed a friend, and found one in Jabar.